A Century of Irish Economic Independence

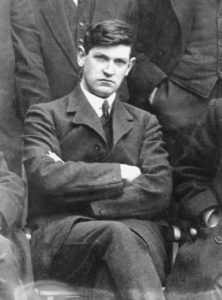

At the Irish Free State’s birth in 1922, hopes were high that independence from Britain – what the 18th century nationalist Theobald Wolfe Tone called “the unfailing source of all our ills” – would lead to greater prosperity. Free State leader Michael Collins said the Irish “were so crushed during the British occupation that they were described as being ‘without the comforts of an English sow’” but “What we hope for in the new Ireland is to have such material welfare as will give the Irish spirit that freedom” to “once more to reach out to the higher things in which the spirit finds its satisfaction.”

But for several decades after independence such hopes went unfulfilled. In 1922, Irish per capita GDP was 56% that of the United Kingdom. By 1943, this had fallen to just 39%, not regaining that relative level until 1969. In 1988, with the ratio 64%, The Economist ran an article on Ireland titled ‘The poorest of the rich’. Why did Ireland stay so poor for so long?

Economic conservatism

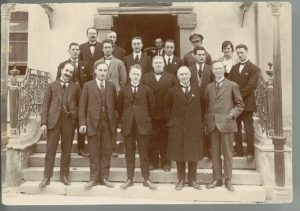

Independence came during a civil war between supporters and opponents of the treaty with Britain, but Ireland avoided the kind of economic collapse that occurred in many of the other countries which emerged after World War One, such as Hungary. This was largely due to the economic conservatism of the new government, composed of the treaty’s supporters, victors in the Civil War (and a powerful, formerly colonizing neighbor anxious for the country to succeed). The economic historian Cormac Ó Gráda wrote:

In what even some of their own supporters deemed a series of U-turns for economic nationalists, the Cumann na nGaedheal government led by Willian T. Cosgrave (1880-1965) rejected industrialization through import substitution and monetary experimentation, and placed its main hopes on a dynamic agricultural sector specializing in livestock and dairying. Partly because of its determination to minimize the debt burden of repairing the physical damage done by the civil war, it ran a very tight fiscal ship.

The result, historian David Fitzpatrick wrote, was that:

Under Cosgrave the Free State had achieved marked improvement in real income per capita despite its unadventurous strategy of balancing the budget, avoiding heavy borrowing, limiting state intervention, and merely dabbling in protective measures against British imports.

Despite or because of?

Economic nationalism

The global depression after 1929 hit Ireland and in 1932’s election Cumann na nGaedheal was defeated by Éamon de Valera’s Fianna Fáil, descendants of the Civil War’s anti-treaty side. Importantly, they handed power over peacefully.

Ó Gráda writes:

In economic policy Fianna Fáil aimed at greater self-sufficiency through the creation of an indigenous manufacturing sector and the switch of agricultural output from livestock towards tillage. For the followers of ‘Dev’ there was no conflict between economic nationalism and job creation: tariff protection would generate much-needed factory jobs and encouraging tilling would tilt the balance away from the ‘grazier’ and towards the smaller farmer and the farm laborer.

Such policies were widespread in the 1930s, but Ireland also launched an ‘economic war’ with Britain when de Valera’s government withheld payments due under the 1922 treaty. The British government retaliated with duties of 20% on Irish agricultural imports, which constituted 90% of all Ireland’s exports, and the Irish economy suffered badly. However, with war looming, the British concluded an agreement ending the ‘war’ in 1938 which permitted de Valera to claim victory.

Though neutral, Ireland’s economy was badly affected by World War Two. A post-war boom was short lived and, Ó Gráda notes, “Real national income virtually stagnated between 1950 and 1958.” “A corrosive pessimism took over,” he writes:

The July 1956 issue of the satirical monthly, Dublin Opinion, bore a cartoon on its cover showing a map of Ireland, with the caption ‘Shortly Available Underdeveloped Country…Owners Going Abroad’…There was an awareness that Irish economic growth was slower than anywhere else in Western Europe.

The primacy of domestic policy

Ireland’s first decade of independence gave it a firmer foundation for prosperity than almost any other country born in the 20th century. True, depression and world war presented a difficult environment for any country, but domestic Irish policy choices after 1932 motivated by what Ó Gráda calls “a nationalist and radical populism” exacerbated this. Compare Fitzpatrick’s description of policy under Cumann na nGaedheal above with economist Brendan Walsh’s of the subsequent period:

If an index of the state’s ‘capacity’ based on its use of [protectionist] instruments as well as on the share of GDP it controlled were developed, there is little doubt that Ireland would come out near the top of the international league table (non-socialist division).

Yet the hopes of the country’s founders went unfulfilled and Ireland’s economy stagnated despite this: or because of?

John Phelan is an Economist at Center of the American Experiment.

Source link